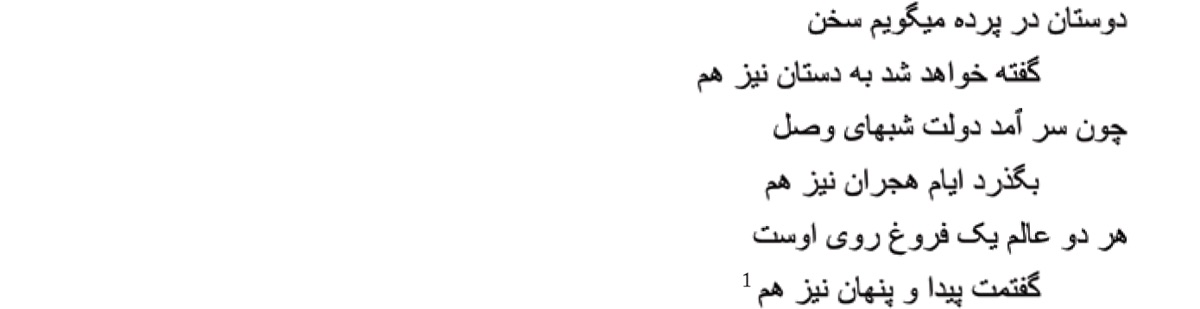

Friends, though my speech is veiled

so too shall revelations be spoken

Just as the nights of union reach their climax

so too shall the days of separation fade away

I say to you, both worlds are the selfsame splendor of the beloved’s face

so too are the manifest and the concealed

EVERY YEAR ON THE VERNAL EQUINOX, my mother opens at random a collection of poems (dīvān) by Hafiz of Shiraz (d. 1389) and reads the first full poem her eyes fall upon. As Persians around the world celebrate this day as the first of the new year, they join my mother in consulting Hafiz, the Voice of the Hidden World (lisān al-ghayb). His poems indicate what the new year holds,2 and readers with the most refined insight can understand the poem’s deepest layers of meaning as prescience. This Hidden World was where God as Truth resided, made potentially accessible through the form and substance of Hafiz’s verses. Like his poetry, which can be read as the celebration of hedonism or union with the divine, this act of consultation has layers of meaning. It is simultaneously a quintessentially Persian act (poetry on the new year) and an act of hermeneutical engagement that defines Islam (supplication to God).3 Far from contradictory, these different meanings are an enduring remnant of what it meant to be Persian before nationalism.

Growing up in a large immigrant enclave in southern California, I was often asked, “Where are you from?” It was an attempt to gain purchase on another question—“Who are you?”—and then, inevitably, “Iranian or Persian?” I was taught to respond, “I am Persian.” Being Persian foregrounded the Persian language and selective elements of its culture, such as pre-Islamic political history and a “classical” poetic tradition that ended with Hafiz in the fourteenth century. This modern selection of culture elided Islam and its supposedly degrading effect on Persian. Claiming a separate identity, it also promoted distance from images of turbaned ayatollahs whipping crowds into a frenzy, of women swathed in black, or of US embassy hostages, who dominated media coverage of Iran in the years after 1979. This culture, however, had come from a place. The term “Persian” and its signifiers—lyrical poetry, epics of mythical kings, and exquisite miniatures from across Asia—became associated with the territory that is now the nation-state of Iran.4

Persians were proud of their culture, which made them better than everyone else. The vaunting of ancient empires and classical art forms, made national, allowed Persians to claim superiority according to a nineteenth-century European system of civilizational hierarchy.5 This valuation, however, was informed by modern, European empires and their attendant racism, and it was structured by capitalism, which exerted the most brutal imperialism the world had ever seen.6 Iranian nationalism revealed the tensions of this new civilizational ideal, which spoke of progress and moral stature but ruled through racial and political domination. In the midst of these tensions, nationalism posited a problematic of civilizational decline—“we” have been great, but we are no longer. In the Pahlavi era, this “we” was a Persian defined by a pure, ancient culture, separate from Islam and focused on the continuous history of the land that came to be modern Iran. These notions of place and origin produced a certain kind of Persian, one who saw those outside this narrow definition as foreign, inferior, and even dangerous.7

Such an articulation of Persian had been formulated over the course of the twentieth century.8 Its most hallucinatory version conceived of Iran before Islam as “secular” by equating Zoroastrian politics and society with post-Enlightenment ideals of human rights and justice, supposedly emancipated from religion. “Classical” poets and thinkers after the advent of Islam somehow lapsed in their religion or overcame its influence, according to a European metric that narrowly equated religion with theology and law alone.9 Hafiz’s appeals to the Unseen realm of Truth bewilderingly became un-Islamic, even as he repeatedly invoked the comforts of reading Qur’an.10

Empirical truth, the most authoritative means of remembering the past, offered limited options for resolving the problem of civilizational decline. Ultimately, while modern Persians became the proud owners of an ancient and grand civilization, Islam remained integral to Iran, which was outside Europe. Persian intellectuals thus turned to European racism, seized upon its concept of Aryanism, and extended it to themselves. For Europeans, Persians had once been Aryans, but the decline of their civilization had divided them from the true heirs of Aryanism in Europe. Persians might claim this heritage, but their “dislocative nationalism” sought a vanishing horizon.11 A relentless urge to laud Persian ways thus vied with claims to superiority based on an unbridgeable distance from those ways.

The exaltation of a pre-Islamic past served to cut Iranians off from both their western and their eastern neighbors, Shi‘a Arabs and Persianate Indians and Central Asians, who were deemed unacceptably similar. This story of a pre-Islamic nation also subordinated more recent, enduring ties of language, culture, circulation, commerce, kinship, and history. Pre-Islamic Persian history was not a new feature of the historiographical tradition. But nationalism took this heritage, severed it from the Islamic history with which it had been harmoniously intertwined, and reconstituted it into a shining story of the nobility and dignity of Persians as Iranians alone. Arabs became savages, Afghans thieves, Indians smelled, and Turks were stupid. These claims to a progressive cultural superiority, based on racism, were strikingly insecure and contradictory.

The main basis of being Persian was language and, as time went on, origin, which meant Persian parents, according to the blood logic of racialized descent. Both language and origin presumed a Persian who was from Iran. What, then, did possessing the Persian language mean before modern nationalism? What did its stories, poetry, aesthetic sense, and above all its proper forms in perceiving, speaking, and acting—its adab—mean in an earlier period? Can we find in those meanings the resources for decolonizing ourselves, for envisioning a future outside the heritage of European colonial modernity? Persianate Selves considers these questions by outlining the meaning of Persian place and origin before nationalism.

Up through the early nineteenth century, Persian was the language of power and learning across Central, South, and West Asia. It was used for poetry, storytelling, government, philosophy, religious instruction, ethical literature, and historical commemoration. Persians were people who had received a particular basic education through which they understood and engaged with the world. Not everyone who lived in the land of Iran was Persian, and Persians lived in many other lands as well.12 Iran, therefore, was not the only significant place, nor were Safavid domains, which included non-Iranian lands and excluded some Iranian lands.13 Similarly, origin was far more expansive than birthplace or parentage.

Persianate selfhood thus encompassed a broader range of possibilities than nationalist claims to place and origin allow. This range of Persianate selves not only challenges nationalist narratives but also reveals a larger Persianate world, where proximities and similarities constituted a logic that distinguished between people while simultaneously accommodating plurality. To be a Persian was to be embedded in a set of connections with people we today consider members of different groups. We cannot grasp these older connections without historicizing our conceptions of place, origin, and selfhood. Yet our hopelessly modern analytic language remains an obstacle.

As my mother’s consulting Hafiz on the new year suggests, aspects of these older possibilities for Persian selfhood remain, even as the modern nation-state has overpowered their logic. What became the Iranian nation (essentially Persian, just as Hindu became essentially Indian) was—and remains—a group of people with multiple languages, affiliations, and collective lineages (what we call ethnicities). The experience of colonial modernity and its appropriation into nationalist frameworks of thought, practice, governance, and aspiration transformed these varieties of Persian into differences and subsumed some within a single nation. Nationalism then rooted these differences in a territory and defined other shared practices and features as foreign, threatening, and in need of suppression. In the process, one kind of Persian was obliterated, and another took shape.

This new type of Persian required a previously unnecessary homogeneity. In contrast, Persians before nationalism certainly had moral hierarchies, and equality was not a vaunted goal. What was Persian remained coherent by allowing equivalences between differences. Rather than homogeneity or equality, what was Persian encompassed symbiosis, multiplicity, relationality, and similitude. Being Persian provided a way to live with, affiliate, and even understand kinship with differing people. Of course, these differences might be insurmountable. The quality of difference, however, was far from absolute and offers a compelling instance of coexistence.

The single most important concept I learned as a child was adab. It was the proper form of things and of being in the world. This concept—of proper aesthetic and ethical forms, of thinking, acting, and speaking, and thus of perceiving, desiring, and experiencing—provided the coherent logic of being Persian. Adab transcended whatever land constituted Iran as a kingdom or nation-state at any given time and sometimes even the Persian language itself.14 Analyzing the period just before the contraction of the Persian language and the rise of modern nationalisms, Persianate Selves elaborates the adab of place and of origin, its forms of meaning, and the possibilities for selfhood that it offered.

The territorial truth of a nation has an obviousness that is deeply contingent historically and politically. Yet even studies that chart nationalism as a historically specific process assume a national territory as transhistorically and objectively identifiable in terms of the empty space of empirical geography. This results in applications of modern notions of culture, society, and geography onto earlier contexts.15 For instance, Kashani-Sabet understands Qajar ideas of Iran, based on Safavid domains, as the latest manifestation of an already constituted Iran reaching back millennia, to pre-Islamic times.16 Such scholarship uncritically adopts this notion from Qajar political narratives, which project an Iran originating from the Sassanian Empire to claim a legitimacy comparable to the Safavids.17 Applying these later formulations of historical continuity to earlier periods, however, essentializes Iran as a timeless and unchanging entity. By contrast, scholars in South Asian studies often make recourse to strikingly modern conceptions of regions, connecting them to vernacular languages and political kingdoms. In arguing for the older (Indian) roots of modern nationalism, as “old patriotism” or “proto-nationalism,” Bayly insists on earlier senses of “rootedness to a particular territory.” He claims, as an example, that the word vatan, which later came to mean the territorial homeland of the nation, “began by meaning the home domain of a particular ruling dynasty.”18 In the pages that follow, I show the untenability of such a simple equivalence of vatan with domain, and the possible ways in which this notion was embedded in broader notions of origin. Bayly’s questioning of scholarly adoptions of modernity’s narrative of rupture is valuable, but his answers do not break free of the same limitations.

In thinking of premodern selves and collectives, Bayly rightly rejects ethnicity as “too imbricated with ideas of blood and race.” But embracing the concept of patriotism, defined as “a historically understood community of laws and institutions fortified by a dense network of social communication generally expressing itself through a common language,”19 reinscribes modern nationalism’s restricted imagining of affiliations and connections. Bayly’s patriotism creates a society’s sense of attachment to a region made homeland through the people’s common language, shared (local) institutions of governance, and regionally specific contingencies (“active social and ideological movements” or “a series of conflicts with outside Others” that are “given ideological meaning and memorialized for future generations”).20 Persianate Selves argues for a different kind of continuity, asking, What about the resolutely smaller meanings of homeland and a shared language that actively linked people across regions and polities?

Geographical essentialism also structures studies focusing on earlier periods, though they locate the national territory in larger cultural worlds or define it as a later articulation of smaller scales (like the region).21 Implicitly, historians tend to treat these future nationalist or colonial borders as definitive notions of origin and thus of collective. Even the most sophisticated scholars, such as Tavakoli-Targhi or Alam, at pains to historicize Persianate culture and society, speak of Iranians and Indians and make reference to an “Indian world” or “Indian psyche” as if the South Asian subcontinent already formed a cohesive whole distinct from other entities such as “Iranians,” “Turko-Persians,” and “Islamic peoples.”22 Although using terms other than Iranian or Indian might render discussion awkward, these concepts need at least to be problematized, so that modern meanings do not structure scholarship. This lack of critical attention results in a methodological and analytic nationalism, in spite of explicitly stated intentions to the contrary.23 Positing Iran and India as the operative categories in the early modern period obfuscates what people shared, as well as the legibility of smaller geographical entities and their ties and distinctions with one another, which could justify different understandings of regional coherence. In the Persianate world, multiple understandings of territorial and cultural boundaries defied nation-states as readily as they prefigured them. Scholars have tended to take historical meanings that resonate with modern outcomes (for example, land as the basis of belonging), separate them from their conceptual apparatus, which included other bases of belonging, and ignore the rest.24

The problem is that we cannot historicize without some self-reflection on our own understandings of place and origin. Modern geography distinguishes interpreted place from physical space.25 Land, space, and territory are deemed objective and self-evident. This logic of empiricism as the sole natural ground of truth is both ubiquitous and anachronistic. It conveys a consistently empty space upon which subjectivities of place are built. In earlier times, however, what we now understand as empiricism was but one form of meaning-making that produced place. For instance, travel between places was defined by the time spent in transit (farsakh) rather than spatial measurement.26 By assuming that land is empirically verifiable and ontologically consistent, with different understandings stemming only from interpretation, we reinscribe narrow, hermeneutical matrices of modern positivism as universal and transhistorical.27 In contrast, we might consider the ways that meanings associated with place could produce materiality, both as impetus to build and as hermeneutics of perception.

Scholarly demarcation of regional fields reinforces these problems. Middle Eastern and South Asian studies reify distinctions historically unjustifiable. Challenges to presumed difference have begun in the context of Iranian and Ottoman studies,28 but reconsideration of linkages across polities comes more easily when two realms are studied as part of the same region (“the Middle East”). Linkages between Iran and South Asia, in contrast, seem to be conceived only as fundamentally foreign influences within an otherwise “native” domain.

Separate treatment of modern Iran and South Asia also stems from the presumed definitive salience of formal colonial experience. The differences that inform national, popular, and scholarly histories, however, have obscured two important similarities. One is centuries of a shared Persianate education, sustained past the advent of colonial rule in India. The other is a shared transformation of self-understanding engendered by the power-knowledge nexus of Orientalist narratives. Though spared formal colonial rule, European colonial domination was integral to the constitution of many aspects of Iranian modernity, including the creation of its borders and the understanding of its history and culture.29 Persian-speaking thinkers, writers, and officials engaged with a broader global dialogue, and European ideas circulating in Egypt, Ottoman domains, and British India.30

The scripts that underpin Iranian and Indian nationalisms are similar. Both depend on narratives about the origin of a people and the shape of a land. In some versions, a glorious ancient past forms the natural core of the nation as the basis of a pure, original culture, society, and political life.31 With Muslim invasions and subsequent rule, this glory dimmed and degenerated. Not all nationalist narratives, even those propagated by the state, were anti-Islamic. Rather, aspects of Islamic civilization could be nationalized through recourse to indigenous ethnicities and “real” kinship.32 Origin was thus racialized (Hindus were Aryans too!). The deleterious effects on the present—whether a result of Islam, political corruption, or societal negligence—were proven by the ease with which Europeans dominated these lands.33 To become worthy of self-rule and national success once more, these scripts explain, Iran and India needed to recover their true national selves, ironically based on historical narratives generated by European powers and appropriated by sons of the nation. A particular understanding of a self and its connections thus engenders political visions and authorizes all manner of actions—from modernization to militarization to exigencies of the state that makes life unlivable for whole groups of people.

Let me put it another way. A commonsensical formulation asserts that Persian is the language of a place called Persia, which has existed since antiquity. This is the nationalist formulation of culture, based on an assumed confluence of territory, people, and language linked by modern notions of native-ness. The mirror image of this formulation holds sway in South Asia, where Persian was the language of Muslim conquerors and thus is inherently foreign. Both of these nationalist narratives rely on modern notions of what is native, what is foreign, and what “naturally” constitutes difference. The foreign-native binary coheres around an idea of home and origin that, in each case, appears empirical and thus objectively true, singular, and mutually exclusive.

Underlying this ostensible mutual exclusivity, however, is a history of commonality and intimacy. For centuries, Persians from Central, South, and West Asia read the same corpus of well-known ethical, literary, and commemorative texts.34 These basic texts, some widely disseminated through oral recitation, gave rise to shared literary tropes, interpretive paradigms, and representational forms. These were also diversely inflected. Most educated Persians had other languages of learning, such as Arabic or Sanskrit, and other vernacular languages such as Chagatai or Braj.35 Nevertheless, Szuppe has argued that “a clear perception of belonging to a single cultural space was maintained over this geographically vast area” (eastern Iran, or Khurasan, Central Asia, and northern India)

for centuries after the “Empire” of Timur’s descendants had disappeared in the years following 1506. This perception derives partly from the use in these regions of the Persian language as the dominant idiom of literary expression, as well as from a common adherence to the Perso-Islamicate cultural-social system of education, behavior, and good manners, or adab, which provided a common basis for the educational and cultural references shared in particular by the literate middle and upper classes of society.36

Through this basic education, a person imbibed proper forms of aesthetic style and ethical conduct (the two faces of adab) that made them Persian.37 These forms changed according to geographical and temporal contingencies, producing variations that lay alongside one another with uneven degrees of comfort.

Despite differing local contexts, these meanings were shared between the educated classes of former Safavid and Timurid domains. Certain local specificities became diffused across regions through sustained circulation of people, texts, and ideas.38 What was Persian thus remained living, breathing, and diverse, not only across religions or regions but also across types of people—courtiers, scholars, poets, merchants, mystics, military leaders, and many who combined these roles. Their perspectives and affiliations differed, even as they shared the means for expressing these differences. A shared basic education bestowed particular forms of place, origin, and proper conduct, creating modes of affiliation constituting selves and community. This commonality did not necessarily lead to agreement about the meanings of places or the relative values of particular origins. Rather, Persians shared a mutually intelligible vocabulary with which they expressed agreement or disagreement, drawn from their shared education. The sometimes conflicting views of Persians in Irani and Hindustani domains thus points to a range of possibilities for connection and affiliation, as well as distance and difference.

To understand common notions of place and origin, we must first embrace a form of meaning-making different from our own. For Persians, categorical differences did not need to be absolute or mutually exclusive. The sensibilities imparted by their basic education were governed by adab (proper form), whose aporetic character allowed for multiplicities of meaning and interpretation within its forms. Concepts were constituted relationally, so that the meanings of place and origin could be multiple and shifting. Elucidating these meanings reveals a different kind of Persianate self, with a range of possibilities. Before nationalism, Persianate selves could hail from many places, and their origins comprised a variety of lineages. The interrelations among these lineages render coherent their multiple modes of imagination, practice, and experience.

For the Islamic, this multiplicity has been called “coherent contradiction,” reconciled through hierarchies of meaning, interdependent and part of the same truth of the unity of God (tawhīd).39 The road to the more valued unseen (bātin) was through and connected to the manifest (zāhir), which was at once superficial and necessary.40 Multiplicities and their tensions were thus necessary, even if ideally transcendable (for some; others could only recognize or merely follow). As Hafiz’s verses in the epigraph show, the unseen and the manifest were part of one Splendor. This cosmology was simultaneously articulated in adab, the proper form of things, as the means and manifestation of the most harmonious, beautiful, and virtuous substance, most perfect and closest to the Truth. Historically, awareness of the multiplicity that hierarchies of meaning allowed produced an understanding of difference as overlapping gradients, rather than as mutual exclusivity. Certain categories of people, for instance, could be from Iran, even as they belonged to India.

Aporia is key here. Formulating categories with discrete borders—like the distinction between text and context or Iranian and Indian—is a way of knowing firmly rooted in modern epistemology. Another logic, however, governs our sources. Persian adab and its defining limits thus present to us moderns as a set of paradoxes. Instead of paradox, I use the term aporia to underline the way in which seeming contradictions appear so through the lens of our present. I borrow Jacques Derrida’s formulation of aporia as a distinction that has “no limit. There is not yet or there is no longer a border to cross, no opposition between two sides: the limit is too porous, permeable and indeterminate.”41 Two categories need not be oppositional; rather “they are articulated with each other; they supplement and engender each other.”42 Thus aporetically defined distinctions create the terms by which social affiliations, their forms, and the articulation of their hermeneutical contours imbued and linked language and practice, the imaginative and the experiential.

To make room for prenationalist Persian self-understandings and their possibilities for connection, I argue against the application of modern notions of ethnicity in historicizing origins of earlier periods. Disavowing Orientalism and its narratives of stagnation and decline require us to consider the immediate premodern past as more than a prelude to modernity. This caveat applies especially to the politically fragmented eighteenth century, which has been disregarded on its own terms in the absence of political glory. More generally, standing in the way of a fresh consideration of the not-so-distant past is a set of modern ideas that have structured scholarly practice. In what follows, I outline concepts that undergird Persianate Selves, to open space for new discussions.

1. Hāfiz Shirāzī, Dīvān-i Hāfiz, 271. Unless otherwise indicated, all translations are my own. I thank Farbod Mirfakhrai for helping me select these verses and for feedback on their translation.

2. Avery, “Foreword: Hāfiz of Shīrāz,” xi. For an overview of his life and work, see Lewisohn, Hafiz and the Religion of Love, especially “Prolegomenon,” 3–73.

3. I utilize Ahmed’s definition of Islam as hermeneutical engagement with the Pre-Text, Text, and Context of Revelation. Here, Hafiz’s Hidden World is engagement with the Pre-Text through a (Persian) poetics as Context, with frequent recourse to the Text (Ahmed, What Is Islam?, 32–38, 345–62, 405–24). Hafiz’s poetry itself came to hold a significant place in the Context of Revelation.

4. On the Iranianization of the Shahnama, for instance, see Tavakoli-Targhi, Refashioning Iran, 96–104.

5. On nineteenth-century discourses of civilization across Europe and Asia, see the essays in Pernau et al., Civilizing Emotions, including Kia, “Moral Refinement and Manhood.”

6. Burbank and Cooper, Empires in World History, 287–329.

7. Zia-Ebrahimi, Emergence of Iranian Nationalism, 1–7. Vejdani demonstrates that the Pahlavi state narrated Islam as a cause of decline only after the Second World War (“The Place of Islam”). Mozaffari details that an alternative Shi‘i collective imagination has existed alongside the pre-Islamic in modern times (Forming National Identity).

8. For recent accounts of twentieth-century nationalism, see Kashani-Sabet, Frontier Fictions; Tavakoli-Targhi, Refashioning Iran; and Marashi, Nationalizing Iran.

9. Ahmed, What Is Islam?, 115–24, 176–82, 187–97.

10. Ibid., 405–8.

11. Zia-Ebrahimi’s outlining of this process is nevertheless relentlessly Eurocentric and modernist in its analytic assumptions. He ignores early modern Iran’s deep imbrication in the world, as well as Persianate and Islamic universalisms’ nuanced relationship to religious difference. Rather, he posits a simplistic “traditional contempt for things ‘infidel,’” a claim he makes courtesy of sources such as consummate Orientalist Bernard Lewis and infamous racist Arthur de Gobineau (Emergence of Iranian Nationalism, 22, quote from 25). This flattening of all things premodern into an impoverished caricature of “traditional” (or medieval) distorts not only an understanding of the early modern but also the substance and meaning of modernity’s changes.

12. For an overview of Persian in South Asia, see Alam, “Culture and Politics of Persian.”

13. Haneda, “Emigration of Iranian Elites,” 130.

14. For an example of Persianate practices of power shorn of their linguistic sheath, see Wagoner, “‘Sultan Among the Hindu Kings’.” He calls these practices in Vijayanagara (in south India) “Islamic-inspired forms and practices” (852–53), though he refers to the same themes in later work as Persian; see Eaton and Wagoner, Power, Memory, Architecture, 3–38.

15. Recent scholarship has made the convincing case that a conception of Iranian nationalism in the sense of a modern nation-state existed only from the mid-nineteenth century and then only among a few elites and intellectuals. The process by which these ideas became dominant was long, uneven, and fitful (see note 8). For South Asian examples, see Chandra, Parties and Politics, xviii; Alam, Crisis of Empire; and Ray, The Felt Community. For a discussion of this tendency in historiography on Iran, see Kia “Imagining Iran,” 89–90.

16. Kashani-Sabet, Frontier Fictions, 15–18. Similarly, see Amanat, Pivot of the Universe, 13.

17. See Amanat, Pivot of the Universe, 2–8, for a discussion of the Qajars’ political conception of the land of Iran. It was in the Qajars’ interest to set themselves up as protectors of the guarded domain of Iran, the latest link in a chain of dynasties to occupy the Iranian throne, abstracting Iran from the Safavids. This notion was especially helpful because Qajars had no charismatic lineage linking them either to the Safavids or to the Prophet (Amanat, “The Kayanid Crown,” 28–29). These early Qajar rulers sought, therefore, to tap into the pre-Islamic millenarian ethos by crafting the imperial character of their rule with such accoutrements as the “Kayanid” crown, which in actual design was a simplified version of the Qizilbash cap. Amanat seems to think this resemblance is something of an accident, even while noting Aqa Muhammad Khan’s post-coronation pilgrimage to Shaykh Safi al-Din’s tomb in Ardabil (22–23).

18. Bayly, Origins of Nationality, 4.

19. Ibid., 11.

20. Ibid., 21. This emphasis on the local as the authentic site of “the people” is also an extremely modern notion, though Bayly also claims that “the bearer[s] of these emergent identities” were both literate Mughal nobles and other “literacy-aware” groups (20). At the very least the presence of multiple meanings (and languages) would complicate the picture.

21. For a valuable study that that relies on the contrast between physical space and interpretive space, see Antrim, Routes and Realms. By contrast, Green understands space as something made. Yet physical features, such as territory and the structures built on them, still stand in contrast to narratives, memory, and imagination (Making Space). Also see Mozaffari on place-making as a process, involving the investment of material sites with layers of meaning (Forming National Identity).

22. Alam, “Culture and Politics of Persian,” 148. Tavakoli-Targhi, Refashioning Iran, 24. Casual references to such entities as “Indian scholars,” meaning Persian-speaking literati of Hindustan, pervade this work. Tavakoli-Targhi also uses Persian interchangeably with Iranian in some places (27), though he clearly means Persian to refer to Persian speakers from either Iran or Hindustan (26). The aim here is not to denigrate Alam and Tavakoli-Targhi’s foundational scholarship but to note that neither analysis utilizes a notion of place with historicized meanings of affiliation or culture.

23. For instance, an excellent general work focusing on political culture between 1200 and 1750 that seeks to present “India as a world region” where “there was constant movement into and out of the subcontinent,” ultimately ends up drawing on modern nationalism’s timeless geographical empiricism. We are told that “the word ‘subcontinent’ used to describe the South Asian landmass highlights the fact that it is a natural physical region separate from the rest of Eurasia.” The authors draw this “natural” boundary to the north by invoking the Himalayas, “beyond which lies the arid and high Tibetan plateau,” which “has largely sealed off access to the subcontinent from the north” (Asher and Talbot, India Before Europe, 5). Yet recent work has shown that this is a colonial vision, taken up by nationalists. Up to the early nineteenth century, northeastern India was intimately connected with Tibet socially, politically, and culturally (see Chatterjee, “Connected Histories”). Such scholarly interventions concede the very conceptual ground to nationalist visions, which limit their impact.

24. An important example of this mode of analysis is Antrim’s book. She makes place, produced through a discourse about an actual physical territory, the primary basis of belonging (Routes and Realms, for instance 1–3, 5–7). Even by her own admission, however, place was not the only basis, thus raising questions of what belonging might look like if we consider land alongside other bases.

25. Tuan, Space and Place, 1–7.

26. The farsakh was a distance measured in a unit of time spent traveling (per hour, approximately six kilometers) (Hinz, “Farsakh”). For examples of variable farsakh measurements according to faster train travel over the same stretch of land in the late nineteenth century, see Sohrabi, Taken for Wonder, 93–94.

27. A recent call to overcome the historical discipline’s allergy to theory has noted the field’s “unquestioned allegiance to ‘ontological realism.’ Central to this epistemology is a commitment to empirical data that serves as a false floor to hold up the assertion that past events are objectively available for discovery, description, and interpretation. Here the tautology is exposed: empiricist methodology enables the rule of this realism while this realism guarantees the success of empiricist methodology” (Kleinberg, Scott, and Wilder, Theses on Theory and History, I.4, emphasis in the original).

28. Mitchell, “Am I My Brother’s Keeper”; Ateş, Ottoman-Iranian Borderlands; Zarinebaf, “Rebels and Renegades” and “From Istanbul to Tabriz”; and Vejdani, “Contesting Nations.”

29. Recent work includes those mentioned in note 8, as well as Vejdani, Making History. For new work on the shared nature of Iranian and Indian modernity, see the articles by Grigor, “Persian Architectural Revivals”; Jabbari, “Making of Modernity”; and Vejdani, “Indo-Iranian.”

30. Bonakdarian, Britain and the Iranian Constitutional Revolution; and Kia, “Indian Friends.”

31. Partha Chatterjee has argued that this colonial narrative was incorporated into nationalist self-fashioning in the context of what he calls the spiritual domain (“Histories and Nations,” in Nation and Its Fragments, 95–115). Scholarship on colonial history has explored the function of these narratives in colonial governance and their absorption into indigenous elite discourse. See Cohn, Colonialism and Its Forms; Mani, Contentious Traditions; Sen, Distant Sovereignty; and Travers, Ideology and Empire. For work dealing with these issues in the Iranian context, see Tavakoli-Targhi, Refashioning Iran; Dabashi, Iran, especially chapter 1; and Marashi, Nationalizing Iran, especially chapter 2. See also Zia-Ebrahimi, “Emissary of the Golden Age.” Vejdani’s recent work problematizes the dominance of this narrative across the Pahlavi period (Making History).

32. Vejdani, “The Place of Islam.” Reformist narratives in the late nineteenth century were not anti-Islamic. See Kia, “Moral Refinement and Manhood.”

33. Chatterjee, “The Nation and Its Pasts,” chapter 4 in Nation and Its Fragments, 76–94.

34. This basic education is outlined in Alam, “Culture and Politics of Persian,” 163 and 166. This education included books widely read across the Persian world, such as Sa‘di’s Gulistan, the most read Persian book of this time (see Kia, “Adab as Literary Form.”)

35. The terms and degree of Sanskrit-Persian intellectual exchange have not received enough attention. Pollock cites social divisions between Brahmins who were Sanskrit scholars and those who learned Persian and entered Timurid service as indications that, apart from some narrow scientific forms of exchange, formal scholarly exchange was not widespread between languages. This assertion, however, does not address the informal reading habits of learned, multilingual individuals who may have been writing in only one language but who were nevertheless engaging in transcultural exchange (Pollock, “Languages of Science,” 35). More recently, Truschke gives an example of the exchange of knowledge through the oral medium of Hindi, which facilitated communication for the translation of Sanskrit literary texts into Persian at Akbar’s court (“Cosmopolitan Encounters”). Similarly, Allison Busch has shown the ways in which Persians’ cultivation of Braj literary and aesthetic culture, itself drawing on Sanskrit, actually blurs the distinction between cosmopolitan and vernacular poetic circulation (Poetry of Kings, 130–65).

36. Szuppe, “Glorious Past,” 41. Her repeated emphasis on a shared culture specifically limited to the eastern part of Iran is belied by at least one of her authors originating in Asadabad (near Hamdan in ‘Iraq-i ‘ajam) and others traveling to Shiraz and Isfahan for study.

37. Adab had specificities relational to context. For a discussion of the centrality of adab to Sufi orders, see Bashir, Sufi Bodies, 78–85.

38. This shared cultural framework seems to have been sustained by regular contacts among individuals, family groups, and social groups functioning within the political units of the post-Timurid space, who “traveled frequently between Central Asia, Iran and India, thus promoting cultural, literary, and spiritual exchanges through direct personal contacts, and generating an overall climate of profound interest in literary trends, accomplishments and production in all parts of the Persianate world” (Szuppe, “Glorious Past,” 41).

39. Ahmed, What Is Islam?, 109, 335–36, 368–77, 397–404. The harmony of unity in seeming contradiction or paradox is elaborated by Melvin-Koushki, “Imperial Talismanic Love.”

40. Ahmed, What Is Islam?, 377–82. He illustrates this concept of connectedness in his reading of the hierarchies of meaning in representations of wine drinking (417–24).

41. Derrida, Aporias, 20. Derrida presents three types of aporia, stating that “the partitioning among multiple figures of aporia does not oppose figures to each other, but instead installs the haunting of the ones in the other” (20). The classification of aporia proceeds according to the definition of the concept itself.

42. Derrida, Aporias, 64.